Fieldwork in Tirunelveli is slowly winding down. It will conclude with a divine quarrel and a reconciliation.

The whole festival has built to this point…it’s swung between union and separation, between Vishnu moving in and out, both of the physical space of the temple and the capacious space of the heart. Watching these rituals unfold has sharpened my understanding…no, I stand corrected, my experience, my anubhava, of the alvar poems. They’ve become poems in three dimensions, full and fleshy.

And yesterday, in the shy dark of dusk, despite (or was it because of) a bone-deep weariness, I felt this–a kind of shaking up of the blood.

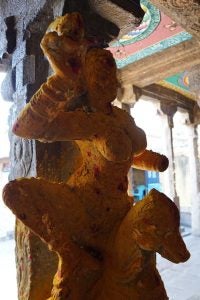

Last night was the Vedpari Utsavam…and it’s when Vishnu finally catches the wily Tirumankai. I was at Srivaikuntham, where Vishnu goes by the appropriate and poetic moniker, Kallappiran–Lord of Scoundrels, Master of Mischief, and boy, does he live up to his name. He comes out on a golden horse (endowed to the temple in 1932), dressed to the nines. And he holds a long spear, shimmering gold that points straight ahead. Sharp and singular.

Tirumankai follows in a smaller palanquin, obscured by the sheer massiveness of the horse. He runs after Vishnu, who clops along at a happy pace. Tirumankai needs to lumber. At some point, Tirumankai races ahead. Now, Vishnu must do the chasing. Eventually, they stand facing each other. I watch this dance in fascination.

Things are about to heat up. Tirumanaki as legend would have it, was a thief. But a devout thief who only stole for the benefit of fellow devotees. A thief nonetheless. Now, Kallappiran, true to his name, decided to make some mischief and have a little fun. He came as a handsome bridegroom and put himself right in the path of the thief who stole for the right reasons. And was robbed blind. Now, the story can take many different turns–but in essence, Tirumankai, is unable to run away with his prodigious loot. He gets mad and accuses the handsome bridegroom of an enchantment. The bridegroom readily admits to this, and promises to reveal the secret. Come close, he says. Tirumankai edges close. No, no, closer, he urges. Still closerclosercloser, till they are so close as to almost be one. The master of the game leans down and whispers eight syllables–his name, the vessel that contains all–and Tirumankai realizes that he’s been bested. The master thief had something to teach him after all.

So, the festival last night unfurled this encounter. That’s what all the chasing is about. Eventually, when they face each other, there is reading of the accounts: you’ve taken necklaces, and pearls, and silks. Do you admit this or not? Tirumankai faced with the magnitude of his thievery, reluctantly admits his guilt. All this was well and good. And I enjoyed the spirit of fun in which this festival unfolded. After all, everything has been so solemn thus far. Grace-giving and Grace-getting always seem such serious work.

And then the air changed. And at the very instant that Tirumankai makes his admission, a great group of men began chanting the opening verse of Tirumankai’s extraordinary work, the Periya Tirumoli. I’ve always had a special place for this section–there is such despair and quiet power in the words: vadinen vadi varundinen: I faded, and fading I suffered.

வாடினேன் வாடி வருந்தினேன் மனத்தால்

பெருந்துயர் இடும்பையில் பிறந்து

கூடினேன் கூடி இளையவர் தம்மோடு

அவர் தரும் கலவியே கருதி

ஓடினேன் ஓடி உய்வது ஓர் பொருளால்

உணர்வெனும் பெரும் பதம் திரிந்து

நாடினேன் நாடி நான் கண்டுகொண்டேன்

நாராயண என்னும் நாமம்-

I sought fulfillment in legions of women, he says, lead astray, intoxicated by pleasure.

And then, I crept closer. I saw all that matters: the syllables that form Narayana. That name.

Last night, I too was speared through the heart.

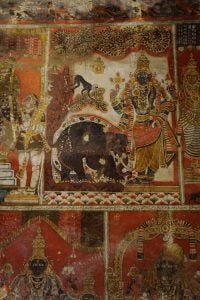

So here he is, Kallappiran, ready for the hunt: