Alvar Moksam (Jan 7, 2018), Ira Pattu, Day 10, Adhyayanotsavam, Day 20.

Here in Tirukkurungudi, Tirumankai receives moksa twice. First, to conclude the pakal pattu utsavam and the recitation of his Periya Tirumoli, then again, at the end of the Ira Pattu Utsavam as the recitation of Nammalvar’s Tiruvaymoli draws to a close. In both cases, he is himself, but is understood as being both Nammalvar and Tirumankai, just as Nammalvar is both Nambi and himself. This duplication, replication, transformation is a theme that I need to return to and explore in greater depth.

The final day is brought to a close with a recitation of the last 100 of the Tiruvaymoli, verses that the commentarial traditions have long held express Nammalvar’s final union with Vishnu. This event is enacted at the end of every Adhyayanotsavam at every Srivaishnava temple, but with always a slightly different flavor. Regardless of what form this enactment takes, the result is always a moment of enormous potency and power, and a deeply, deeply affecting experience for everyone assembled.

At Tirukkurungudi, the recitation of the last hundred moved with brisk, precise efficiency. Until we reached the sixth hundred. After this, at the conclusion of every decad, there was an elaborate tiruvaradhanai and the offering of some delectable naivedya. With each Aradhana, the tension went up just a little bit more. The recitation slowed infinitesimally with each of these aarathis, so that in the end, sound acquired a viscous quality. Each aarathi was waved a little bit more slowly, lingering on the feet, on the face, on the chest with its shining jewel. It was a true light and sound show for the ages.

In the end, they brought Tirumankai out from among where he was with the rest of the alvar. He was lovingly brought to Nambi’s feet and completely immersed in a pile of fresh, green tulasi that rose up like a little hill. The fragrance that filled the air in that moment was exotic and unfamiliar–tulasi, incense, sandal, camphor, the flowers, the food–each distinct in their own way, but mingled together, they produced a scent so unique as to be unreproducible.

As the moksa unfolds, the gosti recites the final ten verses of the Tiruvaymoli and then return us, as the poem intends, once again to the very beginning–uyarvara uyar nalam, to the highest good.

Who possesses the highest, unsurpassable goodness? That one.

Who cuts through confusion and graces the mind with goodness? That one.

Who is the overlord of the immortals who never forget? That one.

at his luminous feet that cut through affliction, bow down and rise, my mind.

Nammalvar. Tiruvaymoli. I.1.1

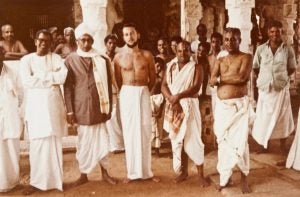

PS. My photographs from yesterday were a bit of a miss. I got some good shots, but I am so relieved that Selva was with me, as I know he got what I missed. It was very difficult to photograph yesterday as there was so much movement, so much happening in different places, and my position did not give me as clear a line as I would have liked. I couldn’t find a steady hand, a steady heart or a steady eye. I found myself really anxious, wanting to make sure I got the photographs I needed. This was the first time I felt this way through the 20 days of the festival, and the anxiety translated itself, predictably, in what came through. In contrast, despite all this anxiety, what I have in my mind’s eye is luminous and clear. I suppose that should suffice. But sometimes it doesn’t. But having another photographer by your side, is a sure comfort.