In 1964, Guy Welbon made his way deep into southern Pandya territory, where he stumbled (in his telling) upon a large, old, beautiful temple. Of course, he fell immediately in love, entranced by the ghats and the god (who is appropriately named The Beautiful Prince). Guy returned to Tirukkurungudi numerous times, with his young family in tow, and got deep into the ritual world of the temple. He wrote a small, important essay on the temple’s Kaisika Natakam–and it’s a boon to us today, for the drama died out in the late 80s, and was revived by Anita Ratnam in the 1990s. But it is much changed now, adapted to accommodate a restless audience and changing expectations and tastes.

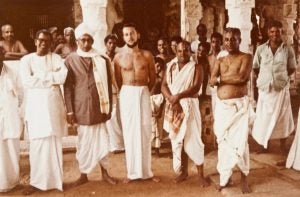

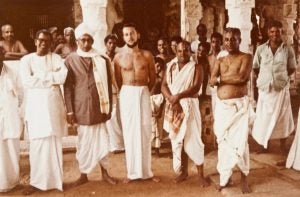

Guy, who was a professor of religion at U-Penn for many years, has amassed an extraordinary archive of Tirukkurungudi. When I wrote to him about my interest in the place, he offered to help and to share his archive. I met him in Philly in early 2018, where he not only shared with me some incredible photographs, but also tales of life in a tiny, insular temple-village in the late 60s, 70s, and 80s. He spoke fondly of his priest friends and of how they would lower him into the temple from the roof so as to avoid the disapproving stares and glares of the village ladies. He had two local artist friends painstakingly hand-copy the inscriptions off the walls. Since he knew no Tamil, he used Sanskrit (!) as his primary means of communication.

In Tirukkurungudi, Guy (who is known only by his last name Welbon), conjoined with his one-time collaborator Martin (so they are Welbon-Martin or Martin-Welbon) has entered the folklore (or the sthala purana, perhaps) of the place. The older denizens recall him vividly and fondly. Most of them are gone, but he is memorialized in their photographs as well.

It’s rare for us to encounter the collector of an unexpected or unintended archive. Guy never meant for his photographs and letters and inscription copies to become an archive–they were his research materials. For some reason or another, he never did publish his rich, rich findings. That is going to be left to us–Crispin, Anna, Leslie and me–to follow through on. It’s rather extraordinary to have Guy at hand to clarify questions. He is himself now an archive, although I do not know if he would think of himself that way.

Below, a photograph from his archive of Alagiya Namabi entering the Kaisika Mantapam, Tirukkurungudi, 1967. Notice the violinist in front of the deity, playing to entertain him. This hereditary role is no longer occupied at the temple. There is a robust nagasvaram player, who commands many instruments, but not the violin.

And here is one, also from Guy Welbon’s archive, of the Kaisikam troupe. Featured are the two devadasis of that temple. They were still performing in 1967, despite the passage of the Devadasi Abolition Act in August 1947. I have yet to find their names–Guy does not recall–and once I do so, I will update that information here.

EDIT: I learned that one of the Devadasis was named Kalyani. I do not know which of the two pictured here. Alas, the other still remains nameless. I shall keep trying to find their names and identify them, lest they be forgotten like so many others like them.